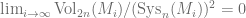

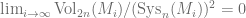

This is a note on Mikhail Katz’s paper (1995) in which he constructed a sequence of Riemannian metrics  on

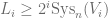

on  s.t.

s.t.  for

for  . Where

. Where  denotes the

denotes the  -systole which is the infimum of volumes of

-systole which is the infimum of volumes of  -dimensional integer cycles representing non-trivial homology classes. To find out more about systoles, here’s a nice 60-second introduction by Katz.

-dimensional integer cycles representing non-trivial homology classes. To find out more about systoles, here’s a nice 60-second introduction by Katz.

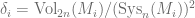

We are interested in whether there is a uniform lower bound for  for

for  being

being  equipped with any Riemann metric. For

equipped with any Riemann metric. For  , it is known that

, it is known that  . Hence the construction gave counterexamples for all

. Hence the construction gave counterexamples for all  . An counterexample for

. An counterexample for  is constructed later using different techniques.

is constructed later using different techniques.

The construction breaks into three parts:

1) Construction a sequence of metrics  on

on  s.t.

s.t.  approaches

approaches  as

as  .

.

2) Choose an appropriate metric  on

on  s.t.

s.t.  equipped with the product metric

equipped with the product metric  satisfy the property

satisfy the property

3) By surgery on  to obtain a sequence of metrics on

to obtain a sequence of metrics on  , denote the resulting manifolds by

, denote the resulting manifolds by  , having the property that

, having the property that

The first two parts are done in previous notes (which are not published on this blog). Here I will talk about how is part 3) done given that we have constructed manifolds  as in part 2).

as in part 2).

Let  equipped with metric

equipped with metric  as constructed in 1),

as constructed in 1),  be as constructed in 2).

be as constructed in 2).

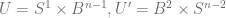

Standard surgery: Let  and let

and let  .

.  . The resulting manifold from standard surgery along

. The resulting manifold from standard surgery along  in

in  is defined to be

is defined to be

which is homeomorphic to

which is homeomorphic to  .

.

We perform the standard surgery on the  component of

component of  , denote the resulting manifold by

, denote the resulting manifold by  . Hence

. Hence  equipped with some metric.

equipped with some metric.

Note that the metric depends on the surgery and so far we have only specified the surgery in the topological sense. Now we are going to construct the surgery taking the metric  into account.

into account.

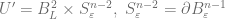

First we pick  to be a small ball of radius

to be a small ball of radius  , call it

, call it  . Pick

. Pick  that fills

that fills  to be a cylinder of length

to be a cylinder of length  for some large

for some large  with a cap

with a cap  on the top. i.e.

on the top. i.e. ![B_L^2 = S^1 \times [0,L] \cup \Sigma](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=B_L%5E2+%3D+S%5E1+%5Ctimes+%5B0%2CL%5D+%5Ccup+%5CSigma&bg=ffffff&fg=5e5e5e&s=0&c=20201002) and

and  . Hence the standard surgery can be performed with

. Hence the standard surgery can be performed with  and

and  . The resulting manifold

. The resulting manifold  is homeomorphic to

is homeomorphic to  and has a metric on it that depends on

and has a metric on it that depends on  and

and  .

.

Let  i.e. the part that’s glued in during the surgery, call it the ‘handle’.

i.e. the part that’s glued in during the surgery, call it the ‘handle’.

The following properties hold:

i) For any fixed  , for

, for  sufficiently small,

sufficiently small,

Since

implies

implies  can be made small by taking

can be made small by taking  small.

small.

ii) The projection of  to its

to its  factor is distance-decreasing.

factor is distance-decreasing.

iii) If we remove the the cap part  from

from  (infact from

(infact from  ), then the remaining part admits a distance-decreasing retraction to

), then the remaining part admits a distance-decreasing retraction to  .

.

i.e. project the long cylinder onto its base on  which is

which is  .

.

iv) Both ii) and iii) remain true if we fill in the last component of  i.e. replace it with

i.e. replace it with  and get a

and get a  -dimensional polyhedron

-dimensional polyhedron  .

.

Since all we did in ii) and iii) is to project along the first and third component simultaneously or to project only the first component, filling in the third component does not effect the distance decreasing in both cases.

We wish to choose an appropriate sequence of  and

and  so that

so that  .

.

In the next part we first fix any  and

and  so that property i) from above holds and write

so that property i) from above holds and write  for

for  .

.

We are first going to bound all cycles with a nonzero ![[S^n]](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5BS%5En%5D&bg=ffffff&fg=5e5e5e&s=0&c=20201002) component and then consider the special case when the cycle is some power of

component and then consider the special case when the cycle is some power of  and this will cover all possible non-trivial cycles.

and this will cover all possible non-trivial cycles.

Claim 1:  -cycle

-cycle  belonging to a class with nonzero

belonging to a class with nonzero ![[S^n]](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5BS%5En%5D&bg=ffffff&fg=5e5e5e&s=0&c=20201002) -component, we have

-component, we have  .

.

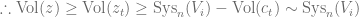

Note that since  and by part 2),

and by part 2),  and by property i),

and by property i),  . Let

. Let  , hence

, hence  . Therefore the bound in claim 1 would imply

. Therefore the bound in claim 1 would imply

which is what we wanted.

which is what we wanted.

Proof:

a) If  does not intersect

does not intersect

In this case the cycle can be “pushed off” the handle to lie in  without increasing the volume. i.e. we apply the retraction from proposition iii).

without increasing the volume. i.e. we apply the retraction from proposition iii).

b) If  then by proposition ii),

then by proposition ii),  projects to its $S^n$ component by a distance-decreasing map and

projects to its $S^n$ component by a distance-decreasing map and  by construction in part 2).

by construction in part 2).

Now suppose  with

with  .

.

Define  s.t.

s.t.  .

.

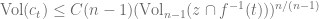

Let  , then by the coarea inequality, we have

, then by the coarea inequality, we have  s.t.

s.t.

.

.

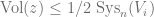

By our results in Gromov[83] and the previous paper of Larry Guth or Wenger’s paper,  s.t.

s.t.  -cycle

-cycle  with

with  ,

,  . Hence

. Hence  with

with  . By picking

. By picking  , we have

, we have  as

as  .

.

Recall that  ; by construction

; by construction  and

and  .

.

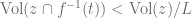

Let ![z_t = z \cap f^{-1}([0,t])](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=z_t+%3D+z+%5Ccap+f%5E%7B-1%7D%28%5B0%2Ct%5D%29&bg=ffffff&fg=5e5e5e&s=0&c=20201002) ,

,

(1) If the cycle  has non-trivial homology in

has non-trivial homology in  , then by proposition iv), the analog of proposition iii) for

, then by proposition iv), the analog of proposition iii) for  implies we may retract

implies we may retract  to

to  without decreasing its volume. Then apply case a) to the cycle after retraction we obtain

without decreasing its volume. Then apply case a) to the cycle after retraction we obtain  .

.

Contradicting the assumption that  .

.

(2) If  has trivial homology in

has trivial homology in  , then

, then  is a cycle with volume smaller than

is a cycle with volume smaller than  that’s contained entirely in

that’s contained entirely in  . By case b),

. By case b),  projects to its

projects to its  factor by a distance decreasing map, and

factor by a distance decreasing map, and  . As above,

. As above,  , contradiction.

, contradiction.

42.054805

-87.676354

s.t.

with

, we have

that’s bi-lipschitz with constant 2 and

?

is defined in the infinitesimal sense, i.e.

.

, does there always exist a map that locally does not deform the metric too much ( i.e. bi-lipschitz with constant

) and “folds” the set into the unit ball.

contained in its

neighborhood) and fold the skeleton instead. Not sure exactly what to do yet…maybe Whitney’s construction? Or construction similar to creating the nerve in Čech homology? Obviously there is a smaller lipschitz constant allowed when we pass to the skeleton, but that might not be an issue since we can pick the measure of our set arbitrarily small.