It’s thanksgiving, let’s have some fun in lantern-making!

This thing called Schwartz lantern initially came up in a talk some years ago, I vaguely remembered it as ‘a cool example where the refining triangle approximation of a smooth surface fail to converge in area’. Anyways, it came up again recently as I was talking to some German postdoc working in ‘discrete differential geometry’. As the example was mentioned, he took a napkin and started folding…and I just realized this lantern can actually be made with a piece of flat paper!

Given a compact, smooth surface (possibly with boundary) embedded in  , we can approximate it by a PL surface with all vertices on the surface and having only triangular faces. (just like what’s done in many computer graphic softwares nowadays).

, we can approximate it by a PL surface with all vertices on the surface and having only triangular faces. (just like what’s done in many computer graphic softwares nowadays).

Question: When the vertices of the faces gets denser and denser and the diameter of triangles converge to  , does the area of the PL surface converge to the area of the surface?

, does the area of the PL surface converge to the area of the surface?

Ok, to explain why I found this being a quite curious little question, let’s prove a couple of trivial observations:

Trivial fact #1: The sequence of PL surfaces as described above does Hausdorff converge to the smooth surface.

Proof:Since our surface is smooth, as the diameter of the triangles converge to  , the length of the geodesic between two vertices is roughly the length of the edge in the 1-skeleton of the PL surface. In particular, less than twice its length.

, the length of the geodesic between two vertices is roughly the length of the edge in the 1-skeleton of the PL surface. In particular, less than twice its length.

Now by compactness we have a positive injectivity radius, implying that for small enough length  , the diameter (on the surface) of region enclosed by any loop of length most

, the diameter (on the surface) of region enclosed by any loop of length most  is controlled by

is controlled by  (say it’s

(say it’s  which converge to

which converge to  as

as  ). Now the

). Now the  diameter of the region is of course even smaller than its surface diameter.

diameter of the region is of course even smaller than its surface diameter.

In conclusion, when all triangles have small diameter  (hence all its sides have length at most

(hence all its sides have length at most  ), the geodesic triangle on the surface has parameter less than

), the geodesic triangle on the surface has parameter less than  . So

. So  diameter of the geodesic triangle is no more than

diameter of the geodesic triangle is no more than  . Hence the surface is contained in the

. Hence the surface is contained in the  -neighbourhood of the vertex set.

-neighbourhood of the vertex set.

Obviously the PL surface is also contained in this neighbourhood. Hence the Hausdorff distance is at most  , which converges to

, which converges to  .

.

Trivial fact #2: For curves in  (in fact, or

(in fact, or  ), the length converges.

), the length converges.

Proof: Well…what can I say…see any undergrad calculus book? (well, all we need is that smooth curves are rectifiable. Of course they are…

So from the above observations, does it kinda smell like the area would converge? (If you know the answer, you should pretend you don’t and nod at this point :-P) Well, the fact is they don’t have to converge! (otherwise why are we making counter-examples here?) Furthermore, this is first discovered by a super-cool dude – Schwartz! He even wrote a paper about it back in 1880.

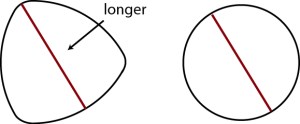

How can this be possible? You might have already observed that with some simple curvature bounding, we can push the argument for trivial fact #1 to show that area of the curved surface is controlled above by the straight surface, The point being (perhaps to one’s surprise) that the ‘straight surface’ can be a lot LARGER than the curved one!

So the example is a sequence of ‘lanterns’ converging to a standard cylinder (say of height and circumference both equal to  ), i.e. PL surfaces with triangular faces, vertices on the cylinder, with smaller and smaller ‘grids’, and the sum of areas of the triangle blows up to infinity.

), i.e. PL surfaces with triangular faces, vertices on the cylinder, with smaller and smaller ‘grids’, and the sum of areas of the triangle blows up to infinity.

As shown above, if we have put  points on the cylinder,

points on the cylinder,  points along the circumference and

points along the circumference and  in the vertical direction (picture is not to scale); connected to form triangles in the above way.

in the vertical direction (picture is not to scale); connected to form triangles in the above way.

Now all triangles are isosceles and identical. Doing some middle-school geometry shows that they have base length  and height

and height  (this calculates the distance between the midpoint of the base to the cylinder surface).

(this calculates the distance between the midpoint of the base to the cylinder surface).

Having  triangles means the area

triangles means the area  of the PL surface is at least

of the PL surface is at least  when

when  large,

large,  . Hence the

. Hence the  blows up to infinity.

blows up to infinity.

Is this pretty cool? This lantern also have an interesting feature that, if we define ‘curvature’ on vertices to be the sum of angles attached to that vertex, (and of course the curvature on the edge between two flat faces shall be  ), then all lanterns have curvature

), then all lanterns have curvature  everywhere, just as in the smooth cylinder! i.e. it can be made by folding a single piece of flat paper.

everywhere, just as in the smooth cylinder! i.e. it can be made by folding a single piece of flat paper.

Let’s note that although the triangles are getting uniformly smaller, they do become ‘thinner and thinner’ in the example. In fact this is the only way it can go wrong, i.e. it can be shown that if we further require the triangles to have bounded eccentricity then the area does converge.

Add-on: I actually made the lantern! They are interesting to fold, aesthetically pleasing and even functional! (you’ll see light flaring out in an interesting way)

Trying it out while one thinks about problems is highly amusing and recommended~

All one needs to do is:

Tips on folding:

1. Be sure to make all diagonal lines positive fold and horizontal lines negative.

2. Make the diagonals cross an even number of horizontals or else after you finish all diagonals, you’ll end up with left and right-facing diagonals not crossing on the horizontal (i.e. you’ll need to double the number of horizontals to make it work again)

3. After finishing all lines, it might be hard at first to make the whole thing ‘fold up’. The trick being to make sure all ‘crosses’ are ‘poped-out’ on the whole surface. The final folding process does not work locally!

4. Although theoretically you can take an arbitrarily long strip of paper with unit width to make unit-sized lantern, but in order to not make a million folds and have super-sharp angles between the diagonal and horizontal; I recommend not being too aggressive on the length :-P (square-ish papers are good enough)

Have fun!~

A not-very-good picture of my lantern (larking light bulb…>.<)

40.343599

-74.651774