In the last lecture of a course on Heegaard splittings, professor Gabai sketched an example due to Hass-Thompson-Thurston of two genus Heegaard splittings of a

-manifold that requires at least

stabilization to make them equivalent. The argument is, in my opinion, very metric-geometric. The connection is so striking (to me) so that I feel necessary to give a brief sketch of it here.

(Side note: This has been a wonderful class! Although I constantly ask stupid questions and appear to be confused from time to time. But in fact it has been very interesting! I should have talked more about it on this blog…Oh well~)

The following note is mostly based on professor Gabai’s lecture, I looked up some details in the original paper ( Hass-Thompson-Thurston ’09 ).

Recall: (well, I understand that I have not talked about Heegaard splittings and stabilizations here before, hence I’ll *try to* give a one minute definition)

A Heegaard splitting of a 3-manifold is a decomposition of the manifold as a union of two handlebodies intersecting at the boundary surface. The genus of the Heegaard splitting is the genus of the boundary surface.

All smooth closed 3-manifolds has Heegaard splitting due the mere existence of a triangulation ( by thicken the 1-skeleton of the triangulation one gets a handlebody perhaps of huge genus, it’s easy exercise to see its complement is also a handlebody). However it is of interest to find what’s the minimal genus of a Heegaard splitting of a given manifold.

Two Heegaard splittings are said to be equivlent if there is an isotopy of the manifold sending one splitting to the other (with boundary gluing map commuting, of course).

A stabilization of a Heegaard splitting is a surgery on

that adds genus (i.e. cut out two discs in

and glue in a handle). Stabilization will increase the genus of the splitting by

)

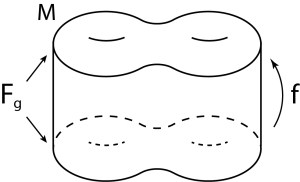

Let be any closed hyperbolic

-manifold that fibres over the circle. (i.e.

is

with the two ends identified by some diffeomorphism

,

):

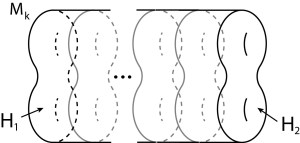

Let be the

fold cover of

along

(i.e. glue together $k$ copies of

all via the map

:

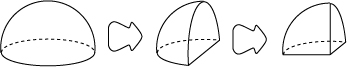

Let be the manifold obtained by cut open

along $F_g$ and glue in two handlebodies

at the ends:

Since is hyperbolic,

is hyperbolic. In fact, for any

we can choose a large enough

so that

can be equipped with a metric having curvature bounded between

and

everywhere.

( I’m obviously no in this, however, intuitively it’s believable because once the hyperbolic part is super large, one should be able to make the metric in

slightly less hyperbolic to make room for fitting in an almost hyperbolic metric at the ends

). For details on this please refer to the original paper. :-P

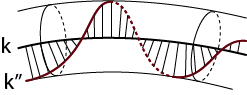

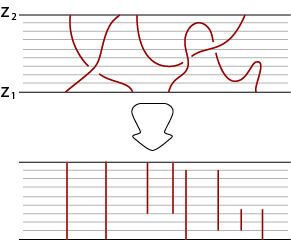

Now there comes our Heegaard splittings of !

Let , let

be the union of handlebody

together with the first

copies of

,

be

with the last

copies of

.

are genus

handlebodies shearing a common surface

in the ‘middle’ of

:

Claim: The Heegaard splitting and

cannot be made equivalent by less than

stabilizations.

In other words, first of all one can not isotope this splitting upside down. Furthermore, adding handles make it easier to turn the new higher genus splitting upside down, but in this particular case we cannot get away with adding anything less than many handles.

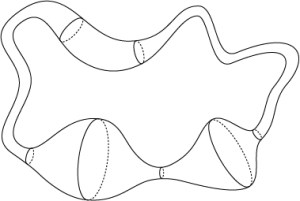

Okay, not comes the punchline: How would one possible prove such thing? Well, as one might have imagined, why did we want to make this manifold close to hyperbolic? Yes, minimal surfaces!

Let’s see…Suppose we have a common stabilization of genus . That would mean that we can sweep through the manifold by a surface of genus (at most)

, with

-skeletons at time

.

Now comes what professor Gabai calls the ‘harmonic magic’: there is a theorem similar to that of Pitts-Rubinstein

Ingredient #1: (roughly thm 6.1 from the paper) For manifolds with curvature close to everywhere, for any given genus

Heegaard splitting

, one can isotope the sweep-out so that each surface in the sweep-out having area

.

I do not know exactly how is this proved. The idea is perhaps try to shrink each surface to a ‘minimal surface’, perhaps creating some singularities harmless in the process.

The ides of the whole arguement is that if we can isotope the Heegaard splittings, we can isotope the whole sweep-out while making the time- sweep-out harmonic for each

. In particular, at each time there is (at least) a surface in the sweep-out family that divides the volume of

in half. Furthermore, the time 1 half-volume-surface is roughly same as the time 0 surface with two sides switched.

We shall see that the surfaces does not have enough genus or volume to do that. (As we can see, there is a family of genus surface, all having volume less than some constant independent of

that does this; Also if we have ni restriction on area, then even a genus

surface can be turned.)

Ingredient #2: For any constant , there is

large enough so no surfaces of genus

and area

inside the middle fibred manifold with boundary

can divide the volume of

in half.

The prove of this is partially based on our all-time favorite: the isoperimetric inequality:

Each Riemannian metric on a closed surface has a linear isoperimetric inequality for 1-chains bounding 2-chains, i.e. any homologically trivial 1-chain

bounds a

chain

where

.

Fitting things together:

Suppose there is (as described above) a family of genus surfaces, each dividing the volume of

in half and flips the two sides of the surface as time goes from

to

.

By ingredient #1, since the family is by construction surfaces from (different) sweep-outs by ‘minimal surfaces’, we have for all

.

Now if we take the two component separated by and intersect them with the left-most

copies of

in

(call it

), at some

,

must also divide the volume of

in half.

Since divides both

and

in half, it must do so also in

.

But is of genus

! So one of

and

has genus

! (say it's

)

Apply ingredient #2, take , there is

large enough so that

, which has area less than

and genus less than

, cannot possibly divide

in half.

Contradiction.