Now we begin to prove the theorem.

4.Attractor-repeller pairs

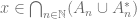

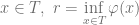

Definition: A compact set  is an attractor for

is an attractor for  if there exists

if there exists  open,

open,  and

and  .

.  is called a basin of attraction.

is called a basin of attraction.

For any attractor  ,

,  be a basin for

be a basin for  , let

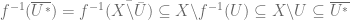

, let  is open. By definition,

is open. By definition,  and

and  . We also have

. We also have

Definition: A repeller for  is an attractor for

is an attractor for  . A basin of repelling for

. A basin of repelling for  is a basin of attracting for

is a basin of attracting for  .

.

Hence  is a repeller for

is a repeller for  with basin

with basin  .

.

It’s easy to see that  is defined independent of the choice of basin for

is defined independent of the choice of basin for  . (Exercise)

. (Exercise)

We call such a pair  an attracting-repelling pair.

an attracting-repelling pair.

The following two properties of attracting-repelling pairs are going to be important for our proof of the theorem.

Proposition 1: There are at most countably many different attractors for  .

.

Proof: Since  is compact metric, there exists countable basis

is compact metric, there exists countable basis  that generates the topology.

that generates the topology.

For any attractor  , any attracting basin

, any attracting basin  of

of  is a union of sets in

is a union of sets in  , i.e.

, i.e.  latex for some subsequence

latex for some subsequence  of

of  .

.

Since  is compact,

is compact,  is an open cover of

is an open cover of  , we have some

, we have some  s.t.

s.t.  covers

covers  .

.

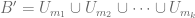

Let  hence

hence  . We have

. We have

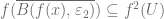

Since  is an attracting basin for

is an attracting basin for  , all three sets are equal. Hence

, all three sets are equal. Hence  . i.e. any attractor is intersection of foreward interates of come finite union of sets in

. i.e. any attractor is intersection of foreward interates of come finite union of sets in  . Since

. Since  is countable, the set of all finite subset of it is coubtable.

is countable, the set of all finite subset of it is coubtable.

Hence there are at most countably many different attractors. This establishes the proposition.

By proposition 1, we let  be a list of all attractors for

be a list of all attractors for  . Now we are going to relate the arrtactor-repeller pairs to the chain recurrent set and chain transitive components.

. Now we are going to relate the arrtactor-repeller pairs to the chain recurrent set and chain transitive components.

Proposition 2:

Proof: i)

This is same as saying for any attractor  ,

,  .

.

For all  , let

, let  be a basin of

be a basin of  , then there is

, then there is  for which

for which  (recall that

(recall that  is the dual basin of

is the dual basin of  for

for  ). Since

). Since  and

and  we conclude

we conclude

Hence  . Let

. Let  be the smallest integer for which

be the smallest integer for which  . Hence

. Hence  . Let

. Let  is also a basin for

is also a basin for  .

.

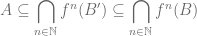

Now we show such  cannot be chain recurrent: Since

cannot be chain recurrent: Since  and

and  are compact and disjoint, we may let

are compact and disjoint, we may let

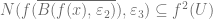

Since  , there exists some

, there exists some  s.t.

s.t.

so there exists

so there exists  s.t.

s.t.

(Here  denotes the ball of radius

denotes the ball of radius  around

around  and

and  denotes the

denotes the  -neignbourhood of compact set

-neignbourhood of compact set  )

)

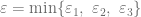

Now set  , for any

, for any  -chain

-chain  , we have: Since

, we have: Since  and

and  ,

,  and

and  . Hence the third term of any such chain must be in

. Hence the third term of any such chain must be in  . Since

. Since  , no

, no  -chain starting at

-chain starting at  can reach

can reach  , in particular, the chain

, in particular, the chain  does not come back to

does not come back to  . Hence we conclude that

. Hence we conclude that  is not chain recurrent. ii)

is not chain recurrent. ii)  Suppose not, there is

Suppose not, there is  and

and  . i.e. for some

. i.e. for some  there is no

there is no  -chain from

-chain from  to itself. Let

to itself. Let  be the open set consisting all points that can be connected from

be the open set consisting all points that can be connected from  by an

by an  -chain.

-chain.

We wish to generate an attractor by  , to do this all we need to check is

, to do this all we need to check is  :

:

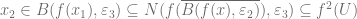

For any  there exists

there exists  with

with  . Since

. Since  , there is

, there is  -chain

-chain  which gives rise to

which gives rise to  -chain

-chain  . Therefore

. Therefore  .

.

Hence  is an attractor with

is an attractor with  as a basin.

as a basin.

By assumption,  , since

, since  and there is no

and there is no  -chain from

-chain from  to itself,

to itself,  cannot be in

cannot be in  . i.e.

. i.e.  Take any limit point

Take any limit point  of

of  , since

, since  is compact

is compact  -invariant we have

-invariant we have  . But since we can find

. But since we can find  where

where  ,

,  gives an

gives an  -chain from

-chain from  to

to  , hence

, hence  .

.

Recall that  is a basin of

is a basin of  hence

hence  is empty. Contradiction. Establishes proposition 2.

is empty. Contradiction. Establishes proposition 2.

This proposition says that to study the chain recurrent set is the same as studying each attractor-repeller pair of the system. But the dynamics is very simple for each such pair as all points not in the pair will move towards the attractor under foreward iterate. We can see that such property is goint to be of importantce for our purpose since the dynamical for each attractor-repeller pair is like the sourse-sink map.

5. Main ingredient

Here we are going to prove a lemma that’s going to produce for us the ‘building blocks’ of our final construction. Namely a function for each attracting-repelling pair that strickly decreases along the orbits not in the pair. In light of proposition  , we should expect to put those functions together to get our complete Lyapunov function.

, we should expect to put those functions together to get our complete Lyapunov function.

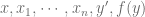

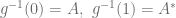

Lemma1: For each attractor-repeller pair  there exists continuous function

there exists continuous function ![g: X \rightarrow [0,1]](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=g%3A+X+%5Crightarrow+%5B0%2C1%5D&bg=ffffff&fg=5e5e5e&s=0&c=20201002) s.t.

s.t.  and

and  for all

for all  .

.

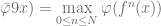

Proof: First we define ![\varphi: X \rightarrow [0,1]](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5Cvarphi%3A+X+%5Crightarrow+%5B0%2C1%5D&bg=ffffff&fg=5e5e5e&s=0&c=20201002) s.t.

s.t.

Note that  takes value

takes value  only on

only on  and

and  only on

only on  . However,

. However,  can’t care less about orbits of

can’t care less about orbits of  .

.

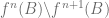

Define  . Hence automatically for all

. Hence automatically for all  ,

,  . Since no points accumulates to

. Since no points accumulates to  under positive iterations, we still have the

under positive iterations, we still have the  and

and  .

.

We now show that  is continuous:

is continuous:

For  and

and  ,

,  and

and  hence

hence  i.e.

i.e.  is continuous on

is continuous on  .

.

For  we use the fact that

we use the fact that  is attracting. Let

is attracting. Let  be a basin of

be a basin of  . For all

. For all  , for any

, for any  , there is

, there is  s.t.

s.t.  . Therefore for some

. Therefore for some  , all

, all  are in

are in  i.e.

i.e.  hence

hence  . But for some

. But for some  and all

and all  ,

,  . Therefore

. Therefore  .

.  is continuous on

is continuous on  .

.

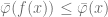

Let  , for any

, for any  , since

, since  , there exists

, there exists  s.t. for all

s.t. for all

![\varphi(f^n(T))\subseteq [0,r/2]](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5Cvarphi%28f%5En%28T%29%29%5Csubseteq+%5B0%2Cr%2F2%5D&bg=ffffff&fg=5e5e5e&s=0&c=20201002) . i.e.

. i.e.  which is countinous. Since those ‘bands’

which is countinous. Since those ‘bands’  partitions the whole

partitions the whole  (by taking

(by taking  to be

to be  ), hence we have proven

), hence we have proven  is continuous on the whole

is continuous on the whole  .

.

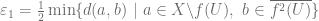

Finally, we define

We check that  is continuous since

is continuous since  is.

is.  takes values

takes values  and

and  only on

only on  and

and  , respectively. For any

, respectively. For any  ,

,

therefore  iff

iff  for all

for all  i.e.

i.e.  is constant on the orbit of

is constant on the orbit of  . But this cannot be since there is a subsequence of

. But this cannot be since there is a subsequence of  converging to some point in

converging to some point in  , continuity of

, continuity of  tells us this constant has to be

tells us this constant has to be  hence

hence  .

.

Therefore  is strictly decreasing along orbits of

is strictly decreasing along orbits of  not in

not in  .

.

Establishes lemma 1.

6.Proof of the main theorem

The proof of the main theorem now follows easily from what we have established so far.

First we restate the fundamental theorem of dynamical systems:

Theorem: Complete Lyapunov function exists for any homeomorphisms on compact metric spaces.

Proof: First we enumerate the countably many attractors as  . For each

. For each  , we have function

, we have function  where

where  is

is  on

on  ,

,  on

on  and is strictly decreasing on

and is strictly decreasing on  .

.

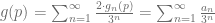

Define  by

by

Since each  is bounded between

is bounded between  and

and  , the sequence of partial sums converge uniformly. Hence the limit function

, the sequence of partial sums converge uniformly. Hence the limit function  is continuous.

is continuous.

For points  , we have

, we have  for all

for all  . i.e. $latex \ \forall n \in \N, \ g_n(p) = 0$ or

. i.e. $latex \ \forall n \in \N, \ g_n(p) = 0$ or  . Hence we have

. Hence we have

where each  is in

is in  . This is same as saying the base-

. This is same as saying the base- expansion of

expansion of  only contains digits

only contains digits  and

and  . We conclude

. We conclude  where

where  is the standard middle-third Cantor set in

is the standard middle-third Cantor set in ![[0, 1]](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5B0%2C+1%5D&bg=ffffff&fg=5e5e5e&s=0&c=20201002) . i.e.

. i.e.  is compact and nowhere dense in

is compact and nowhere dense in  .

.

For  , there exists

, there exists  such that

such that  , hence

, hence  . This implies

. This implies  since

since  for all

for all  . i.e.

. i.e.  is strictly decreasing along orbits that are not chain recurrent.

is strictly decreasing along orbits that are not chain recurrent.

To show  is constant only on the chain-transitive components, we need the following lemma:

is constant only on the chain-transitive components, we need the following lemma:

Claim:  are in the same chain-transitive component iff there is no attracting-repelling pair

are in the same chain-transitive component iff there is no attracting-repelling pair  where one of

where one of  is in

is in  while the other in

while the other in  .

.

Proof (of claim): ” ” Suppose

” Suppose  and

and  , for any attractor

, for any attractor  , if

, if  and

and  , then

, then  are both in

are both in  and we are done. Hence suppose at least one of

and we are done. Hence suppose at least one of  is in

is in  . W.L.O.G. suppose

. W.L.O.G. suppose  . Let

. Let  be a basin of

be a basin of  . Since

. Since  are closed and disjoint, we may choose

are closed and disjoint, we may choose  . By the same arguement as in proposition

. By the same arguement as in proposition  , there are no

, there are no  -chain (with length

-chain (with length  ) from any point in

) from any point in  to any point in

to any point in  . Hence there is also no

. Hence there is also no  -chain from any point in

-chain from any point in  to any point in

to any point in  . Hence

. Hence  i.e.

i.e.  .

.

” ” Suppose for any attractor

” Suppose for any attractor  ,

,  iff

iff  . For any

. For any  , let

, let  be the set of all points

be the set of all points  for which there is an

for which there is an  -chain from

-chain from  to

to  , as defined in proposition

, as defined in proposition  . We have showed in proposition

. We have showed in proposition  that

that  is a basin of some attractor

is a basin of some attractor  . Since

. Since  and

and  , hence

, hence  . Hence by our assumption,

. Hence by our assumption,  must be also in

must be also in  . Hence

. Hence  i.e. there is an

i.e. there is an  -chain from

-chain from  to

to  . Since the construction is symetric, we may also show there is an

. Since the construction is symetric, we may also show there is an  -chain from

-chain from  to

to  . i.e.

. i.e.  .

.

Establishes the claim.

Finally, for  ,

,  means

means  and

and  has the same base-

has the same base- expansion in the Cantor set. This is same as saying

expansion in the Cantor set. This is same as saying  , which is to say there is no

, which is to say there is no  for which one of

for which one of  is in

is in  while the other in

while the other in  . Hence by Lemma, we conclude that

. Hence by Lemma, we conclude that  iff

iff  are in the same chain transitive component.

are in the same chain transitive component.

This establishes our theorem.

42.054805

-87.676354

be a diffeomorphism. A point

is non-wandering if for all neighborhood

of

, there is increasing sequence

where

. We write

.

, for any

. For all

there exists diffeomorphism

s.t.

and

for some

.

,

is compact, then for any

, there exists

,

s.t.

.

.

where

or

. Iterate the above process. since the sequence is at least one term shorter after each shortening, the process stops in finite time. We obtain final sequence

s.t. for all

,

.

times,

, after the first shortening,

.

. Along the same line, we have, at the

-th shortening, the distance between the initial and final sequence and

is at most

. Hence for the final sequence

.

where

by a factor of

w.r.t. the center) and for all

.

in

i.e. find

with

and

id. Hence

.

are the lengths of

,

.

.

, it's at least

away from the boundary of

. i.e. there exists bump function

satisfying the above condition and

.

, we need about

such bump functions, to move a distance

, we need about

bumps.

is a surface. By starting with an

(and hence

) very small, we have for all

is contained in a small neighbourhood of

. Hence on

is

close to the linear map

. Hence mod some details we may reduce to the case where

is linear in a neighborhood of

.

, we can have

preserving the horizontal and vertical foliations and the horizontal vectors eventually grow more rapidly than the vertical vectors.

to be long and thin such that for all

,

has height greater than width. (note that

bumps will be able to move the point by a distance equal to the width of the original rectangle

. Since horizontal vectors eventually grow more rapidly than the vertical vectors, there exists

s.t. for all

,

has width greater than its height.

, the boxes

are disjoint for

. Construct

to be identity outside of

boxes, we let

preserve the horizontal foliation and move along the width so that

has the property that

lies on the same vertical fiber as

.

, we let

pushes along the vertical direction so that

,

.

.

of

.

, we may further perturb

to move

to

. This takes care of the linear case on surfaces.