Recently I came across a paper by John Pardon – a senior undergrad here at Princeton; in which he answered a question by Gromov regarding “knot distortion”. I found the paper being pretty cool, hence I wish to highlight the ideas here and perhaps give a more pictorial exposition.

This version is a bit different from one in the paper and is the improved version he had after taking some suggestions from professor Gabai. (and the bound was improved to a linear one)

Definition: Given a rectifiable Jordan curve , the distortion of

is defined as

.

i.e. the maximum ratio between distance on the curve and the distance after embedding. Indeed one should think of this as measuring how much the embedding ‘distort’ the metric.

Given knot , define the distortion of

to be the infimum of distortion over all possible embedding of

:

It was (somewhat surprisingly) an open problem whether there exists knots with arbitrarily large distortion.

Question: (Gromov ’83) Does there exist a sequence of knots where

?

Now comes the main result in the paper: (In fact he proved a more general version with knots on genus surfaces, for simplicity of notation I would focus only on torus knots)

Theorem: (Pardon) For the torus knot , we have

.

To prove this, let’s make a few observations first:

First, fix a standard embedding of in

(say the surface obtained by rotating the unit circle centered at

around the

-axis:

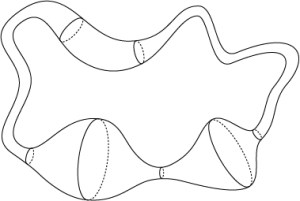

and we shall consider the knot that evenly warps around the standard torus the ‘standard knot’ (here’s what the ‘standard

knot looks like:

By definition, an ’embedding of the knot’, is a homeomorphism that carries the standard

to the ‘distorted knot’. Hence the knot will lie on the image of the torus (perhaps badly distorted):

For the rest of the post, we denote by

and

by

, w.l.o.g. we also suppose

.

Definition: A set is inessential if it contains no homotopically non-trivial loop on

.

Some important facts:

Fact 1: Any homotopically non-trivial loop on that bounds a disc disjoint from

intersects

at least

times. (hence the same holds for the embedded copy

).

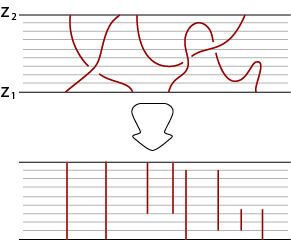

As an example, here’s what happens to the two generators of (they have at least

and

intersections with

respectively:

From there we should expect all loops to have at least that many intersections.

Fact 2: For any curve and any cylinder set

where

is in the

-plane, let

we have:

i.e. The length of a curve in the cylinder set is at least the integral over -axis of the intersection number with the level-discs.

This is merely saying the curve is longer than its ‘vertical variation’:

Similarly, by considering variation in the radial direction, we also have

Proof of the theorem

Now suppose , we find an embedding

with

.

For any point , let

is inessential

i.e. one should consider as the smallest radius around

so that the whole ‘genus’ of

lies in

.

It’s easy to see that is a positive Lipschitz function on

that blows up at infinity. Hence the minimum value is achieved. Pick

where

is minimized.

Rescale the whole so that

is at the origin and

.

Since (and note distortion is invariant under scaling), we have

Hence by fact 2,

i.e. There exists where the intersection number is less or equal to the average. i.e.

We will drive a contradiction by showing there exists with

.

Let , since

By fact 2, there exists s.t.

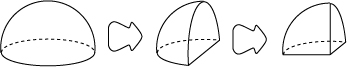

. As in the pervious post, we call

a ‘neck’ and the solid upper and lower ‘hemispheres’ separated by the neck are

.

Claim: One of is inessential.

Proof: We now construct a ‘cutting homotopy’ of the sphere

:

i.e. for each is a sphere; at

it splits to two spheres. (the space between the upper and lower halves is only there for easier visualization)

Note that during the whole process the intersection number is monotonically increasing. Since

, it increases no more than

.

Observe that under such ‘cutting homotopy’, is inessential then

is also inessential. (to ‘cut through the genus’ requires at least

many intersections at some stage of the cutting process, but we have less than

many interesections)

Since is disconnected, the ‘genus’ can only lie in one of the spheres, we have one of

is inessential. Establishes the claim.

We now apply the process again to the ‘essential’ hemisphere to find a neck in the direction, i.e.cutting the hemisphere in half in

direction, then the

-direction:

The last cutting homotopy has at most many intersections, hence has inessential complement.

Hence at the end we have an approximate ball with each side having length at most

, this shape certainly lies inside some ball of radius

.

Let the center of the -ball be

. Since the complement of the

ball intersects

in an inessential set, we have

is inessential. i.e.

Contradiction.