About a year ago, I came up with an simple argument for the following simple theorem that appeared in a paper of professor Guth’s:

Theorem: If is an open set in the plane with area

, then there is a continuous function

from

to the reals, so that each level set of

has length at most

.

Recently a question of somewhat similar spirit came up in a talk of his:

Question: Let be a Riemannian metric on the torus with total volume

, does there always exist a function

s.t. each level set of

has length at most

?

I have some rough thoughts about how might a similar argument on the torus look like, hence I guess it would be a good idea to review and (somewhat carefully) write down the original argument. Since our final goal now is to see how things work on a torus (or other manifolds), here I would only present the less tedious version where is bounded and all boundary components of

are smooth Jordan curves. Here it goes:

Proof: Note that if a projection of in any direction has length (one-dimensional measure)

, then by taking

to be the projection in the orthogonal direction, all level sets are straight with length

(see image below).

Hence we can assume any -dimensional projection of

has length

. A typically bad set would ‘span’ a long range in all directions with small area, it can contain ‘holes’ and being not connected:

Project onto

and

-axis, by translating

, we assume

. Look at the measure

set

in the middle of

(i.e. a measure 1 set

with the property

)

By Fubini, since the volume is at most

, there must be a point

with

:

Since the boundary of is smooth, we may find a very small neighborhood

where for each

. (we will call this pink region a ‘neck’ of the set for it has small width and is roughly in the middle)

Now we define a that straches the neck to fit in a long thin tube (note that in general

may not be connected, but everything is still well-defined and the argument does go through.) and then bend the neck to make the top chunk vertically disjoint from the bottom chunk.

We can take so that

sends the vertical foliation of

to the following foliation in

(note that here we drew the neck wider for easier viewing, in fact the horizontal lines are VERY dense in the neck).

If the -projection of the top or bottom chunk is larger than

, we repeat the above process t the chunks. i.e. Finding a neck in the middle measure

set in the chunk, starch the neck and shift the top chunk, this process is guaranteed to terminate in at most

steps. The final

sends

to something like:

Where each chunk has -width

between

and

.

Define .

Claim: For any .

The vertical line intersects

in at most one chunk and two necks, taking

of the intersection, this is a PL curve

with one vertical segment and two horizontal segment in

:

The total length of is less than

(length of

on the vertical segment)

(length of

on each horizontal segment). Pick

both less than

, we conclude

.

Establishes the theorem.

Remark:More generally,any open set of volume has such function with fibers having length

. T he argument generalizes by looking at the middle set length

set of each chunk.

Moving to the torus

Now let’s look at the problem on , by the uniformization theorem we have a flat torus

where

is a lattice,

and a function

s.t.

is isometric to

.

is the flat metric. Hence we only need to find a map on

with short fibers.

Note that

and the length of the curve from

to

in

is

.

Consider as the parallelogram given by

with sides identified. w.l.o.g. assume one side is parallel to the

-axis. Let

be a linear transformation preserving the horizontal foliation and sends the parallelogram to a rectangle.

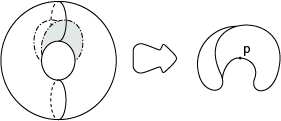

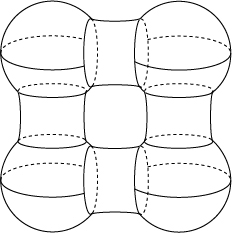

Let be a piece-wise isometry that “folds” the rectangle:

(note that is four-to-one except for on the edges and the two medians)

Since all corresponding edges are identified, $lates F$ is continuous not only on the rectangle but on the rectangular torus.

Now we consider , pre-image of typical horizontal and vertical lines in the small rectangle are union of two parallel loops:

Note that vertical loops might be very long in the flat due to the shear while the horizontal is always the width.

(to be continued)