I have recently went through professor Gabai’s wonderful paper that gives a proof of the tameness conjecture. (This one is a simplified version of the argument given in Gabai and Calegari, where everything is done in the smooth category instead of PL). It’s been a quite exciting reading with many amazing ideas, hence I decided to write a summary from my childish viewpoint (as someone who knew nothing about the subject beforehand).

We say a manifold is tame if it an be embedded in a compact manifold s.t. the closure of the embedding is the whole compact manifold.

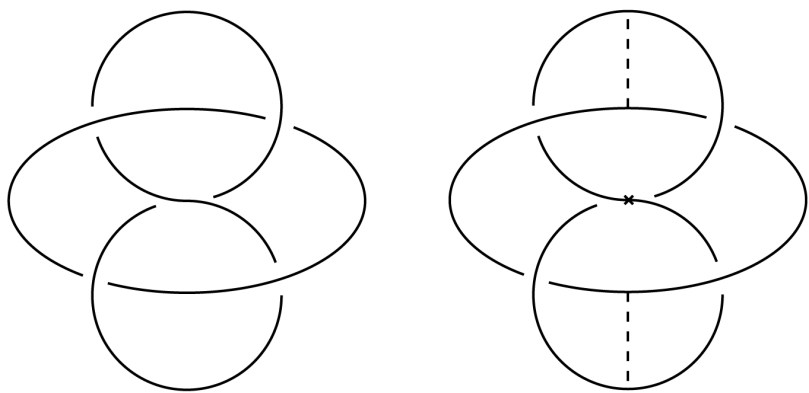

To motivate the concept, let’s look at surfaces: Any compact surface is, of course, tame. However, if we “shoot out” a few points of the surface to infinity, as the figure below, it become non-compact but still tame, as we can embed the infinite tube to a disk without a point.

Of course, we can also make a surface non-compact by shooting any closed subset to infinity (e.g. a Cantor set), but such construction will always result in a tame surface. (This can be realized using similar embeddings as above, we may embed the resulting surface into the original surface with image being the original surface subtract the closed set. If the closed set has interior, we further contract each interior components.)

On the other hand, any surface with infinite genus would be non-tame since if there is an embedding into a compact set, the image of ‘genesis’ would have limit points, which will force the compact space fail to be a manifold at that point.

Hence in spirit, being tame means that although the manifold may not be compact itself, but all topology happens in bounded regions (we can think of a complete embedding of the manifold into some so bounded make sense)

As usual, life gets more complicated for three-manifolds.

Tameness conjecture: Every complete hyperbolic 3-manifold with finitely generated fundamental group is tame.

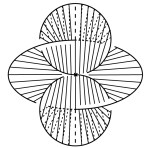

A bubble chart for capturing the structure of the proof:

A few highlights of the proof: The key idea here is shrinkwrapping, very roughly speaking, to prove an geometrically infinite end is tame one needs to find a sequence of simplicial hyperbolic surfaces exiting at the end. Bonahon’s theorem gives us a sequence of closed geodesics exiting the end. By various pervious results, one is able to produce (topological) surfaces that are ‘in between’ those geodesics. Shrinkwrapping takes the given surface and shrinks it until it’s ‘tightly wrapped’ around the given sequence of geodesics. The fact that each of the curve the surface is wrapping around is a geodesic guarantees the resulting surface simplicial hyperbolic. (think of this as folding a piece of paper along a curve would effect its curvature, but alone a straight line would not; geodesics are like straight lines).

Once we have that, the remaining part would be showing the position of the surfaces are under control so that they would exit the end. Since simplicial hyperbolic surfaces has curvature , by Gauss-Bonnet they have uniformly bounded area (given our surfaces also has bounded genus). By passing to a subsequence, we may choose the sequence of geodesics to be separated by some uniform constant, which will guarantee the wrapped surfaces are not too thin in the thick parts of the manifold, hence we have control over the diameter of the surface, from which we can conclude that the surfaces must exit the manifold.

Remark: Note that in general, unlike in two dimensions, a three manifold with finitely generated fundamental group does not need to be tame as the Whitehead manifold is homotopic to (hence trivial fundamental group) but is not tame. On the other hand, if we have infinitely generated fundamental group, then the manifold can never be tame. The theorem says all examples of non-tame manifolds with finitely generated fundamental group does not admit hyperbolic structure.